Nike and Ambush Marketing at the Olympics

Introduction

In the pressurised world of Olympic advertising, where companies spend millions to officially sponsor major events, ambush marketing has evolved as a controversial and clever tactic. It's a strategy where brands attempt to associate themselves with high-profile sporting occasions and capitalise on their visibility, audience, and excitement without paying the official rights fees. These campaigns often blur the lines of legality, walking a fine line between smart marketing and creating unethical commercial competition.

Learning Objective

· To analyse the ambush strategies of a major global brand amid the evolution of regulatory changes.

Nike and the art of Ambush Marketing

Nike has a long tradition of sponsoring athletes and maintaining a high Olympic profile despite its ‘non-sponsorship’ status to the Games. With no official rights, the company has regularly decided to engage in a practice called ‘Ambush Marketing’ to fully capitalise on the global visibility and media attention on offer. According to some critics, Nike has ‘ambushed’ rival brands since the Los Angeles 1984 Games, when they aired TV ads featuring Olympic athletes and used Randy Newman’s song ‘I Love LA’ as a soundtrack.

Nike and the Atlanta 1996 Olympic Games

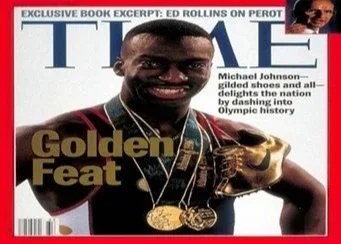

In the summer of 1996, as the world was about to explode with ‘Girl Power’, the Atlanta Olympic Games will be remembered for legendary boxer Muhammad Ali lighting the opening ceremony cauldron and for Michael Johnson, who became the first person to win both the 200m and 400m races at a single Olympics. However, it will also be remembered for the marketing activity of the global brand, Nike, which would help define and reshape Olympic advertising legislation for future generations. With Reebok investing upwards of $40 million for exclusive rights, Nike still managed to dominate the event’s branding and media presence through the following activities:

· The Billboard Blitz: Strategic billboard advertisements across the city created the impression of official involvement. The omnipresence of Nike branding gave spectators and media little choice but to associate the brand with the event.

· The Transport Takeover: Nike extended their reach to public transport. These mobile billboards ensured constant brand visibility to Olympic spectators and those following the games on television.

· The Nike Village: The brand created an experiential village near the Olympic venues, a hub of exclusive product activity that drew visitors and attention. Furthermore, high-profile athletes visited the village, attracting crowds and further associating the brand with the games. These appearances generated media coverage, amplifying the perception that Nike was integral to the Olympic experience.

‘All that Glitters’ is Gold Shoes:

Perhaps the most memorable example is how Michael Johnson’s $30,000 gold shoes became a symbol of the games during his world recording breaking runs. The shoes were impossible to miss, ensuring Nike’s presence in a historic moment.

Nike and the London 2012 Olympic Games

In the summer of 2012, the London Olympics aimed to “Inspire a Generation” of people into sports participation and promote the value of sustainability into future event management. As Queen Elizabeth II and James Bond officially declared the Games open alongside an artistic spectacle celebrating British culture and history, Nike had launched their own creative ‘Ambush’ strategy. With Adidas investing more than $150m for an official sponsorship rights deal the competition was about to become as fierce off the track as it was on it.

· The ‘Volt’: The introduction of Nike’s Volt footwear to over 400 athletes was something that few spectators could miss seeing. A ‘sea of bright yellow shoes’ dominated the running tracks. Their distinctive and ubiquitous neon colour created a stunning visual effect, and the massive numbers of athletes wearing them enhanced this effect even further. Nike’s marketing ‘success’ was based on a loophole in the regulations as shoes were classified as equipment, which athletes could not be banned from wearing, even if provided by non-sponsor brand.

· Find Your Greatness: On the eve of competition, Nike launched an inspiring video campaign entitled ‘Find Your Greatness’ that managed to steal the limelight from Adidas. Nike tested the limits of Olympic rules on ambush marketing by depicting everyday athletes competing in places from around the world named ‘London’. London in Ohio, London in Norway, East London in South Africa, Little London in Jamaica, and Small London in Nigeria.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X0JdbZEKz7k

Conclusion

Official sponsors often see the appearance of their rivals’ logo at major events as an attempt to create confusion, but this is not necessarily wrong or illegal behaviour. Companies such as Nike have the right to promote their own athletes or team associations, without official sponsorship rights. However, even though these types of marketing practices are not breaching any actual legal regulation, they are still seen as unacceptable for host cities that depend on sponsorship money to stage the Games.

Subsequently, Rule 40 of the Olympic Charter established key principles to outline how competitors, team members, coaches, trainers, and officials participating in the Olympic Games can engage in and benefit from commercial activities.

https://img.olympics.com/images/image/private/w_auto/primary/neoqkcdfnjrfxha0i7ob

The rule originates from the amateur origins but has been retained, partly, to protect official sponsors who get very minimal in-stadia branding and there are no sponsor logos permitted on the athletes’ kit (other than the manufacturer). As such, the value of an Olympic sponsorship is mainly gained through advertising association. As the athletes are the ‘face’ of the Games, being able to exclusively align with Olympians during the event sets sponsors apart from their competitors.

In the past, ambush marketing was thought of as a ‘devious, unethical tactic’ or an ‘unfair marketing practice’. However, this opinion has changed, and it is now recognized as a legitimate marketing practice. While the merits of being an ambush brand are clear, these benefits are essentially achieved at the expense of the official sponsors and the host event organizers. The logical consequence is that organisations may lose interest in sponsoring events such as the Olympics, who rely on heavy commercial income to exist. This problem, however, does not seem to bother Nike as rebelling against the system and challenging convention is simply a part of the brand image they try to project.

Reflective Questions for Students

· Why has Ambush Marketing evolved and grown as a commercial strategy over the last 20 years?

· Why is it important for rights holders of major events to develop strict legislation against the practice of Ambush Marketing?

· What are the challenges for Ambusher brands?

· What would you advise official sponsors of major events, considering the continued threat of Ambush Marketing?

Suggested Supplementary Materials

· Burton and Chadwick (2009) Ambush marketing in sport: An analysis of sponsorship protection means and counter-ambush measures. Journal of Sponsorship 2 (4), 303-315.· https://youtu.be/KzKHdfyo0SY?si=G3SwAd0TTV8vhxKu · https://www.olympics.com/athlete365/topics/rule-40 · https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/ambush-marketing-a-threat-to-corporate-sponsorship